Dialogue is one of those marmite things that you either love writing or hate writing. I’ve noticed that writers who love writing dialogue (e.g. me) tend to write a bit like scriptwriters. I often write the first draft of scenes in pure dialogue, and I can reach the end of the scene without ever deciding if these characters are indoors or outdoors, under the sea or on the moon, wearing wetsuits or PJs.

I hate writing physical description of places, people or actions and I usually have to go back when I’ve finished the scene and fill all that in. I like spoken words and the stuff going on inside the character’s head, but not so much the external world.

Whereas I’ve found writers who hate writing dialogue tend to be quite good at world-building and will write whole scenes where you can smell every flower and feel every fold of fabric and see every blade of grass, and stuff does happen but there isn’t a word of dialogue in the whole scene.

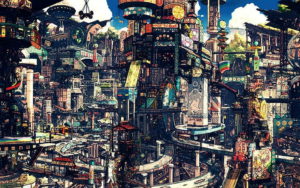

I have never been good at world-building which is why I couldn’t write fantasy. I like the normal world because I can assume readers know what it looks like and how it functions and I don’t have to bother explaining it too much. The reason fantasy books are allowed to be so much longer than non-fantasy books is because they have to create unfamiliar worlds for the reader.

There’s a writer in our group who is so brilliant at world building and visualising things that she not only writes fantasy worlds, she also draws them. One day she was showing me some sketches for a planet she’d invented. It was a sort of exploded globe with flat disks in the middle (see what I mean about my powers of description), and I said, ‘Wow, that’s amazing! Do the disks in the middle spin?’

She shook her head and said, ‘No. They were going to, but then I realised that would interfere with the plumbing.’

‘You’ve thought about the plumbing! I can write a whole scene and I don’t know if my characters are indoors or out and you’ve thought about the plumbing?!!!’

Anyway, this girl is an amazing writer and has the most incredible imagination I’ve ever come across, but she hates writing dialogue and will avoid it if at all possible. But you usually need a bit of both in a story. Pages of unbroken text can be off-putting for a reader and pages of solid dialogue can leave them feeling distanced from the world of the story.

I found some tips online for writing dialogue to help my young writer, so I’m posting them here for all your dialogue-avoiders too. I like it when things are broken down into bullet points so these are lists of “Tips for Writing Dialogue” that you can print out for your group in case anyone’s struggling with it:

- Sarah Webb is an Irish children’s writer and powerhouse promoter of children’s lit and she’s posted her 10 Tips for Dialogue here.

- NY Book Editors 5 Tips for Good Dialogue

- 5 tips from a screenwriter on writing dialogue

- This “6 Tips for Dialogue” article also has a section on how to format dialogue, but that’s really aimed at professional writers and I never comment on this with my writers unless they ask. In fact, most of the adult writers I know still don’t know how to format dialogue, but no book ever got turned down by a publisher because the writer put the commas in the wrong place. Leave that to the English classes and let them enjoy the writing.

And my own advice is just to pay attention to how dialogue is done in books. The thing about good dialogue is it’s invisible. The reason we use ‘she said,’ rather than, ‘she pronounced in a grating monotone’, is that it doesn’t draw attention to itself, allowing the reader to forget that they’re reading something and more fully enter that world. But the result is, we don’t notice how it’s done and then when we come to writing it, we think we don’t know how to do it. So reading a book and paying attention to the dialogue is a great way to learn how to do it. Yay, reading!